Une bonne vision est un outil puissant pour améliorer les résultats scolaires, les opportunités de vie, la participation sociale et la productivité économique future (Burton et al., 2021).

Par conséquent, l'accès à des soins oculaires de qualité est particulièrement important pour les enfants d'âge scolaire et constitue un problème de santé publique significatif, notamment dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire où l'accès à des services de soins oculaires complets peut être limité.

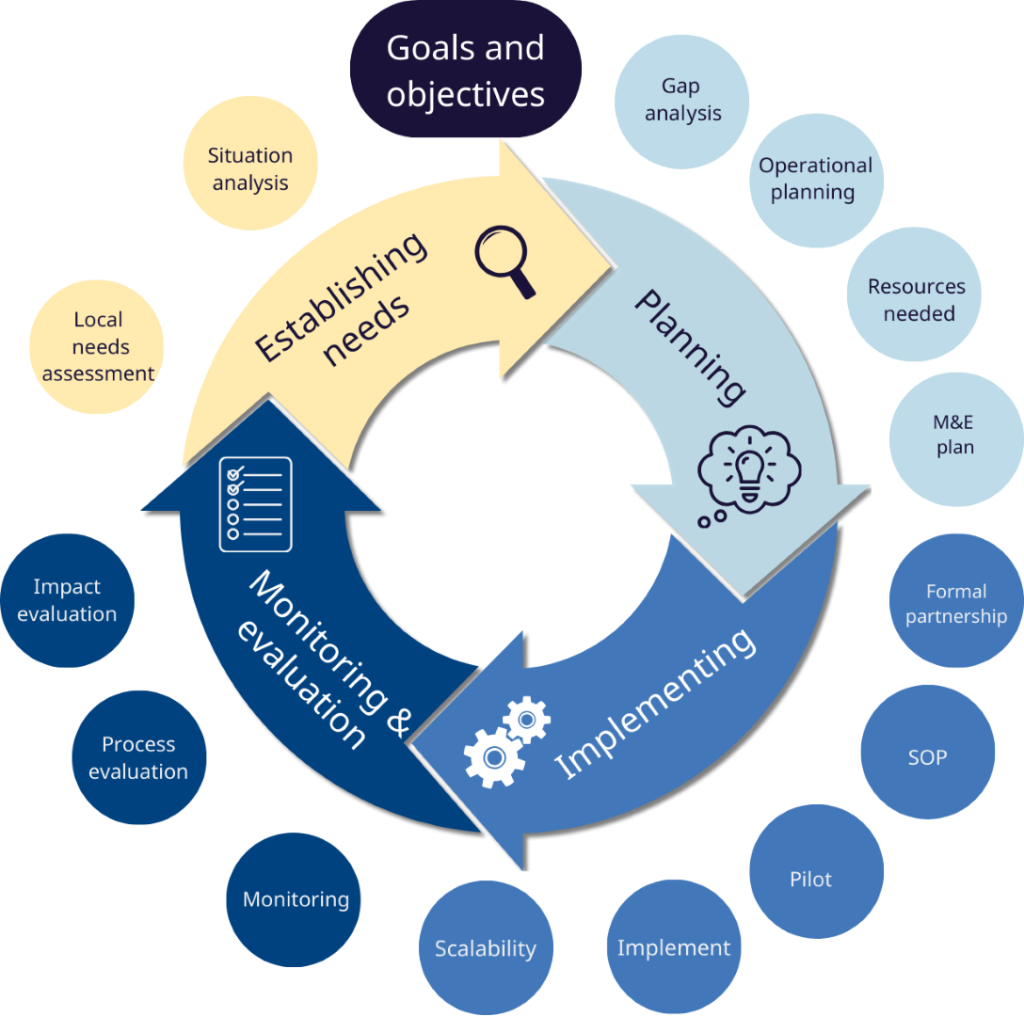

Les programmes de santé oculaire en milieu scolaire peuvent constituer des interventions rentables et efficaces dans de nombreux contextes, car ils permettent de détecter, de diagnostiquer et de traiter les affections des yeux des enfants, principalement les erreurs de réfraction non corrigées (Burton et al., 2021).