For World Glaucoma Week, Dr Desirée Murray, Lecturer in Ophthalmology at The University of the West Indies on challenges in preventing blindness and visual impairment from glaucoma in Trinidad and Tobago.

Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma (OAG) include African ancestry, age, higher intraocular pressure (IOP), and family history of glaucoma, thinner central corneal thickness and myopia. The Caribbean population is predominantly of African descent and are among the countries with the highest prevalence of glaucoma in the world.

Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma (OAG) include African ancestry, age, higher intraocular pressure (IOP), and family history of glaucoma, thinner central corneal thickness and myopia. The Caribbean population is predominantly of African descent and are among the countries with the highest prevalence of glaucoma in the world.

A population-based study in St. Lucia reported a prevalence of OAG of 8.8% in persons 30 years of age or older, compared to a pooled global prevalence of 3.54% for populations aged 40-80 years (1, 2). In Trinidad and Tobago, the age and gender-standardized prevalence of blindness in persons aged >40 years was 0.80% (3), with glaucoma the leading cause of presenting blindness (32%) followed by cataract (29%) and diabetic retinopathy (13%). In Barbados, the prevalence of OAG in persons aged 40- 84 years was 7.0% in black participants (4). At 9-year follow-up, 53% of new OAG cases were undetected (5). Glaucoma was the leading cause of blindness, with 28.4% of blindness due to OAG (6). In Suriname, in persons >50 years, glaucoma (23.8%) was the second most common cause of blindness and the most common cause in men (41.4%) (7).

In 2007, the Caribbean region pioneered the first summit of heads of government on chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs), known as the Port-of-Spain declaration (8). It was acknowledged that

“the burdens of NCDs can be reduced by comprehensive and integrated preventive and control strategies at the individual, family, community, national and regional levels and through collaborative programmes, partnerships and policies supported by governments, private sectors, NGOs and our other social, regional and international partners.”

However, glaucoma wasn’t included as a chronic NCD. Despite irrefutable evidence of its impact it has been largely excluded from the national and regional discourse on chronic NCDs, with cataract and diabetic retinopathy attracting most attention.

The major challenge I face as a consultant ophthalmologist practising in the Caribbean where resources are limited, is increasing attention to preventing glaucoma blindness without diverting these limited resources from other important causes. I believe that the answer lies in both community and health provider education.

Challenges

Community unawareness manifests as:

- Patients with glaucoma presenting with advanced disease including extensive visual field loss and poor vision in at least one eye.

- High non-attendance rate within the public Hospital Eye Service.

- High non-adherence to medication (eye drops).

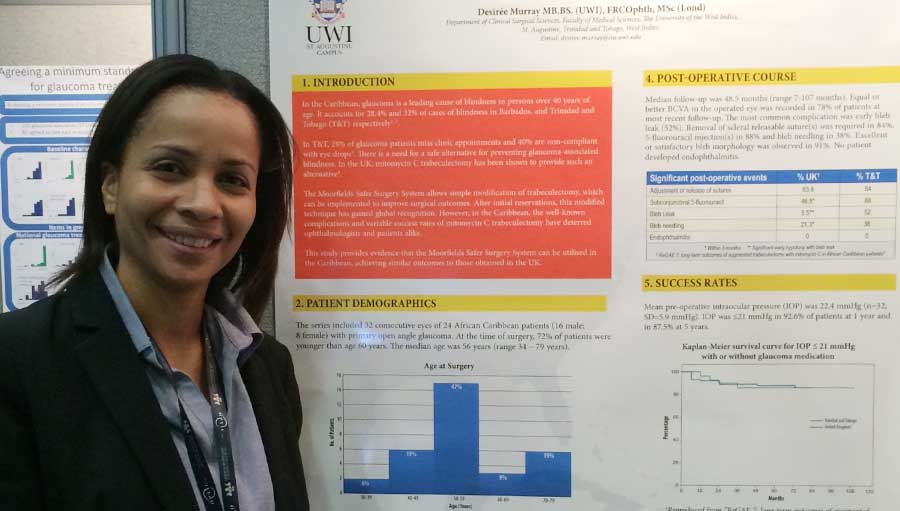

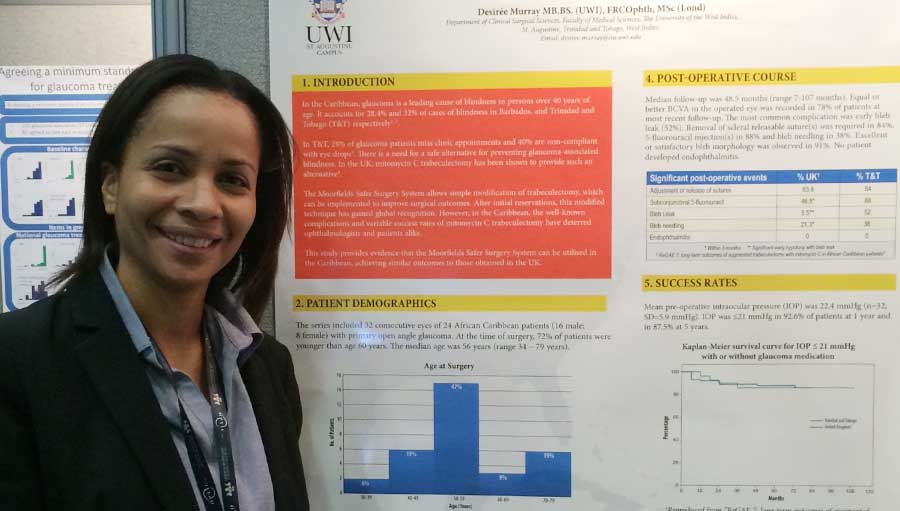

- Patients’ aversion to surgical intervention, although trabeculectomy + Mitomycin C (Moorfields Safer Surgery System) is available and results comparable to best-published world data have been achieved in Trinidad and Tobago (presented as a poster at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists Annual Congress, UK, May 2016).

Health provider inattention manifests as:

- An unreliable supply and/or unaffordability of medication leading to poor adherence and failure of medical treatment.

- A low glaucoma surgical rate due to poor uptake by surgeons.

Solutions

In my view the solutions lie in community involvement and medical education:

- Promote eye health and blindness prevention at the individual, family, community, national and regional levels.

- Integrate eye care at the community services level through the education and training of district health visitors, nurses, primary care physicians and community groups.

- Provide eye care equipment, including visual acuity charts and low budget portable electronic technology, in the community health centres: train and employ staff to use hand-held tonometers and portable hand-held fundus cameras.

- Address uncorrected refractive error in the community with glaucoma screening being linked to the provision of free or subsidized spectacles. This will have an impact on uptake and health-seeking behaviour:

- Include refractive services as part of any cataract surgery programme in our aging population.

- Establish a procurement system designed to make spectacles and low vision aids affordable.

- Provide free or subsidized reading glasses for presbyopia correction.

- Reduce cost sharing and out-of-pocket spending by patients for glaucoma eye drops.

- Introduce ophthalmic nursing as a specialty within nursing.

- Formulate national guidelines for the assessment and management of glaucoma including guidelines for surgical intervention.

- Introduce continuing medical education of eye care professionals.

- Set national targets for service activity.

Late presentation and poor health seeking behaviour may be explained by poor access to reliable and relevant health information. Access to health information is lowest among society’s most vulnerable population groups (9). Empowering patients with knowledge about the major causes of preventable blindness may have a significant impact. Other issue are suboptimal access, uptake and delivery of glaucoma care and a low glaucoma surgical rate linked to these factors.

Blindness and visual impairment, the major causes being glaucoma, cataract, diabetes and uncorrected refractive error, should be recognized as a chronic NCD and should and need to be included in the national conversation on chronic NCDs.

Image on top: Dr Desiree Murray presenting a poster at the RCOphth Annual Congress, Birmingham, UK, May 2016

References

- Mason RP, Kosoko O, Wilson MR, Martone JF, Cowan CL, Gear JC, et al. National survey of the prevalence and risk factors of glaucoma in St. Lucia, West Indies: Part I. Prevalence findings. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(9):1363-8.

- Tham Y-C, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng C-Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081-90.

- Braithwaite T, Bartholomew D, Deomansingh F, Fraser A, Maharaj V, Bridgemohan P, Sharma S, Singh D, Ramsewak SS, Bourne RR; for the NESTT Study Group. The National Eye Survey of Trinidad and Tobago: Prevalence and Causes of Blindness and Vision Impairment. West Indian Med J 2015;64(Suppl. 3):14.

- Leske MC, Connell A, Schachat AP, Hyman L. The Barbados Eye Study: prevalence of open angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112(6):821-9.

- Leske MC, Wu S, Honkanen R, Nemesure B, Schachat A, Hyman L, et al. Nine-year incidence of open-angle glaucoma in the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(6):1058-64.

- Hyman L, Wu S-Y, Connell AMS, Schachat A, Nemesure B, Hennis A, et al. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in the Barbados eye study1 1The authors have no proprietary interest in the articles or devices mentioned herein. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(10):1751-6.

- Minderhoud J, Pawiroredjo JC, Themen H, Bueno dM-VA, Siban MR, Forster-Pawiroredjo CM, et al. Blindness and Visual Impairment in the Republic of Suriname. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(10):2147.

- Declaration of Port-of-Spain: Uniting to stop the epidemic of chronic NCDs 2007 [Posted in: Statements from CARICOM Meetings | 16 September 2007 | Release Ref #: NA | 2226 [Available from: https://caricom.org/media-center/communications/statements-from-caricom-meetings/declaration-of-port-of-spain-uniting-to-stop-the-epidemic-of-chronic-ncds. Accessed 10 March, 2018.

- Kelley MS, Su D, Britigan DH. Disparities in Health Information Access: Results of a County-Wide Survey and Implications for Health Communication. Health Communication. 2016;31(5):575-82.

Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma (OAG) include African ancestry, age, higher intraocular pressure (IOP), and family history of glaucoma, thinner central corneal thickness and myopia. The Caribbean population is predominantly of African descent and are among the countries with the highest prevalence of glaucoma in the world.

Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma (OAG) include African ancestry, age, higher intraocular pressure (IOP), and family history of glaucoma, thinner central corneal thickness and myopia. The Caribbean population is predominantly of African descent and are among the countries with the highest prevalence of glaucoma in the world.